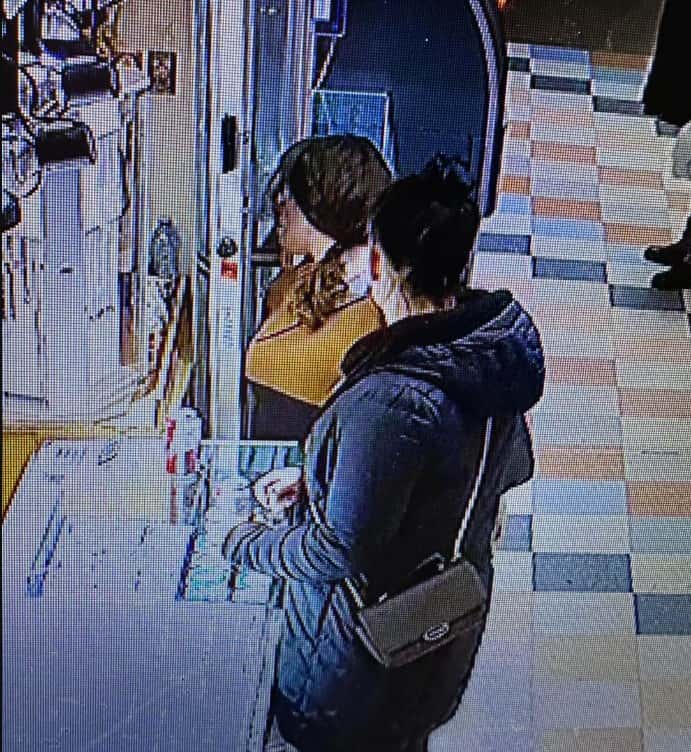

Prashant Sreekumar walked into the Grey Nuns Hospital on Monday with crushing chest pain. He told staff it was a 15 out of 10. They ran an ECG, said nothing looked concerning, and offered him Tylenol.

Then they told him to wait.

Eight hours later, the 44-year-old accountant was finally called into the treatment area. He sat down. Ten seconds passed. He put his hand on his chest, looked at his father, and collapsed.

He never got up.

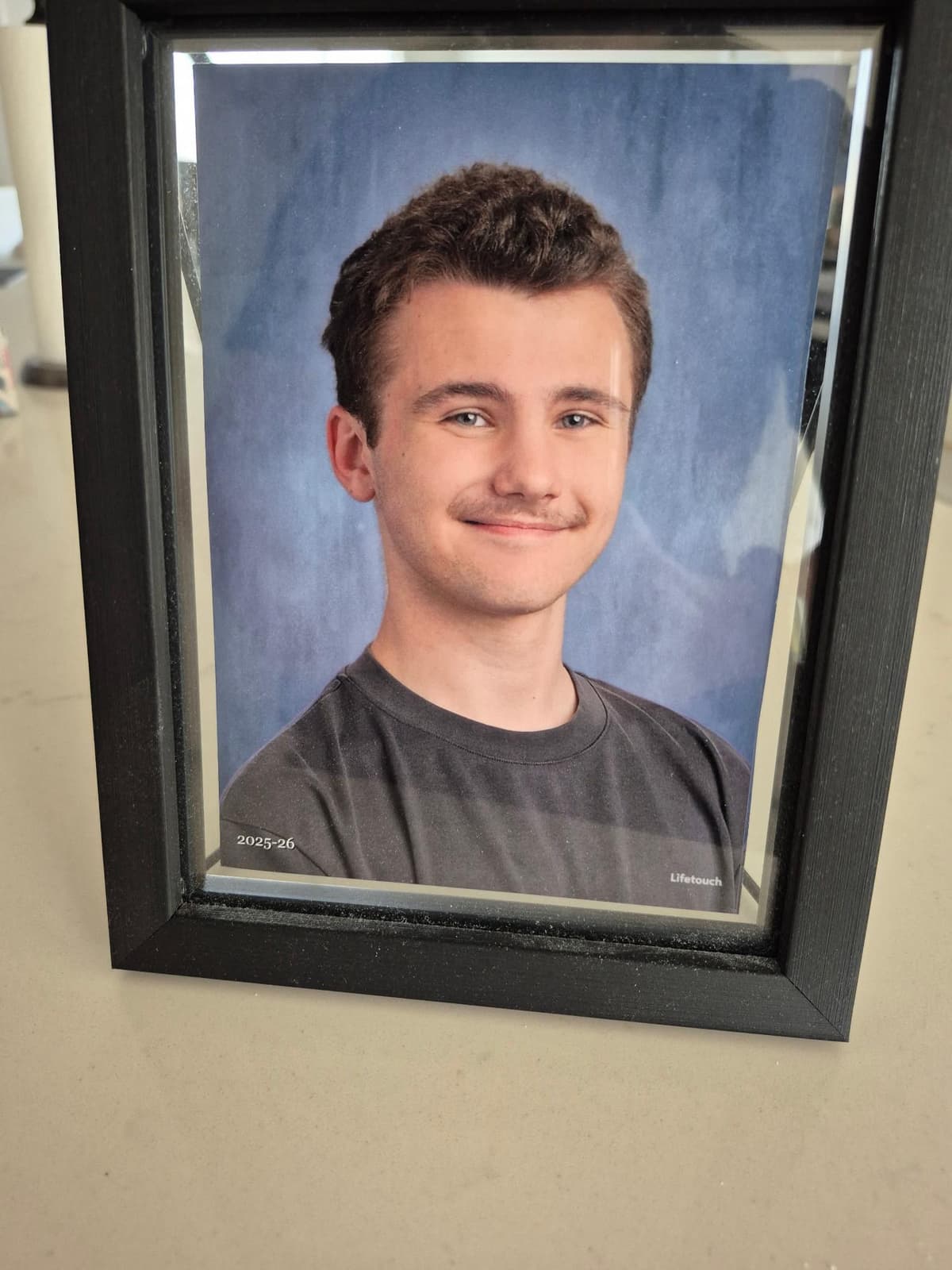

Sreekumar leaves behind a wife and three kids ages 3, 10, and 14. His family says he was a goofball with his children, that he loved to travel, that everyone who met him said he was one of the nicest people they knew.

Now they're planning a funeral and asking how a man with textbook cardiac symptoms could sit in a waiting room until his heart gave out.

His father watched the whole thing

Kumar Sreekumar rushed to the hospital after hearing his son had been brought in. He sat with him in the waiting room as hours ticked by.

"He told me, 'Papa, I cannot bear the pain,'" Kumar said.

He watched nurses check his son's blood pressure. It kept climbing. Through the roof, he said.

And still, nothing happened.

"They took my baby for nothing. For nothing."

The Grey Nuns hasn't seen a new hospital neighbour since 1988

Here's the thing most Edmontonians don't realize: the Grey Nuns Community Hospital, where Sreekumar died, is the last adult hospital built in the city. It opened in 1988.

That was 37 years ago.

Edmonton's population has exploded since then. South Edmonton especially. And for years, there was supposed to be relief on the way a new 491-bed hospital near Ellerslie Road and 127 Street, announced by the NDP government in 2017 and slated to open by 2026.

Then the UCP took power.

First they delayed it to 2030. Then, in February 2024, Health Minister Adriana LaGrange said they were "pausing" the project. A few days later, the provincial budget confirmed there was no money for it at all.

The province had already spent $69 million on the site. Pipes are sitting in piles on the ground. The field is still empty.

Edmonton is hundreds of beds short and it's getting worse

Internal Alberta Health Services documents show the Edmonton zone is currently short by at least 418 hospital beds. By 2026, that number is projected to hit nearly 1,500.

And this isn't just an Edmonton problem.

Just days before Sreekumar's death, a memo leaked to CBC News revealed Calgary's emergency rooms were operating in what officials called "critical overcapacity." Doctors were being told to make decisions on whether to admit or discharge patients within four hours because there simply wasn't room.

One Calgary ER physician described patients with chest pain leaving without being seen and later dying.

Sound familiar?

It's not the staff. It's the system.

One Edmonton healthcare worker explained what's really going on. When you arrive at an ER, you're assigned a triage score 1 means you're actively dying, 2 means urgent but stable. Sreekumar was likely a 2. Problem is, in a packed waiting room, dozens of other 2s arrived before him. And while he waited, 1s kept rolling in overdoses, car crashes, cardiac arrests.

There are only 143 ICU beds in Edmonton. For 1.58 million people.

Nurses are taking 5 to 10 patients at a time. Units are putting people in hallways and offices. Staff are burned out and leaving.

"It's not just an emergency room problem," the worker wrote. "It's a whole healthcare system emergency."

And they believe it's deliberate: "The current government wants a private healthcare system. Easiest way to achieve this, with public support, is to make the public system absolutely horrifying

The UCP's healthcare gamble isn't paying off

When Danielle Smith became Premier, she promised to fix Alberta's healthcare system within 90 days. Instead, her government blew up Alberta Health Services and split it into four separate agencies each with its own CEO, its own minister, its own bureaucracy.

Health policy experts have called it a recipe for disintegration.

The province slashed its flu vaccine campaign. It paused hospital construction. It leaned into private surgical clinics that critics say are poaching staff from the public system without meaningfully reducing wait times.

Meanwhile, Albertans are sitting in waiting rooms for 8, 10, 15, sometimes 20 hours.

Some of them aren't making it home.

The question nobody wants to answer

Prashant Sreekumar did everything right. He went to the hospital when he felt chest pain. He told them how bad it was. He waited where they told him to wait.

And the system failed him.

His family wants answers. So do a lot of Albertans watching emergency rooms buckle under pressure while the government insists its reforms are working.

Covenant Health, which operates the Grey Nuns, said it couldn't comment on specifics due to privacy, but offered condolences. The case is now with the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner.

For Kumar Sreekumar, none of that brings his son back.

"He was for his family, for his kids, he was so nice. Anybody who talked to him said, 'We don't know a better man than him.'"