There's a stretch of northeast Calgary where the prairie sky meets something unexpected a 97-foot steel minaret rising above the suburban rooftops of Castleridge. This isn't Dubai or Istanbul. This is cowboy country, oil patch territory, the land of Stampede breakfasts and chinook winds. And yet, here stands Baitun Nur, the largest mosque in Canada.

The name means "House of Light" in Arabic. The massive steel dome catches the afternoon sun and throws it back at you. It's the kind of structure that makes you stop your car.

More Than a Place of Worship

Walk into Baitun Nur expecting a quiet prayer hall and you'll be surprised. This place runs like a small town.

The 48,000 square foot complex houses a full gymnasium where basketball leagues run year-round. There's a library stocked with texts in multiple languages. A commercial kitchen feeds community dinners and stocks a food bank that serves families across northeast Calgary. Classrooms host youth programs, language classes, and marriage counselling sessions.

But the real showstopper? Canada Day.

Every July 1st, the Ahmadiyya community throws what many locals consider the biggest Canada Day celebration in Calgary. Thousands show up. There's food, music, and the kind of neighbourhood energy that's increasingly rare. Mention "the Canada Day event" in this part of town and people know exactly which one you're talking about.

Fifteen Million Dollars, Raised One Dollar at a Time

Here's what gets me about this story: the $15 million construction cost came almost entirely from the pockets of local community members. No government grants. No wealthy foreign donors writing cheques from overseas. Just ordinary Calgarians teachers, engineers, small business owners digging deep.

One man, Azher Chaudhary, contributed $1.4 million of his own money. When asked about it, he called it an "investment to God."

The mosque was designed by Naseer Ahmad and Manu Chugh Architects. For Ahmad, this was his seventh Ahmadiyya mosque he knew exactly how to balance traditional Islamic aesthetics with the practical needs of a Canadian winter. The result is 48,000 square feet of worship space, classrooms, a gymnasium, a full commercial kitchen, and a community hall that can seat 500.

Construction took just two years. Industry insiders said a comparable project would normally cost many times more. But when your entire community shows up to volunteer, amazing things happen.

July 5, 2008: An Unlikely Guest List

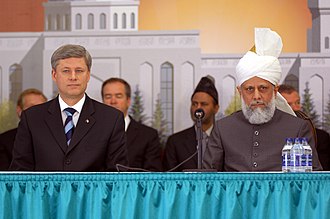

The grand opening drew 5,000 people under white tents on a summer Saturday. But it was the guest list that raised eyebrows.

Prime Minister Stephen Harper showed up. So did Opposition Leader Stéphane Dion. Calgary's mayor at the time, Dave Bronconnier, was there. And in a gesture that still resonates with the community, Roman Catholic Bishop Fred Henry attended as well.

Harper's words that day cut straight to the point: "Calgarians, Albertans and Canadians will see the moderate, benevolent face of Islam in this mosque and the people who worship here."

For a community that had been declared non-Muslim by the government of their homeland, hearing a Canadian Prime Minister validate their faith on their own soil carried weight that's hard to overstate.

More Than a Mosque

Drop by Baitun Nur on any given week and you'll find more than prayers happening. The place functions as a community nerve centre youth programs, marriage counselling, interfaith dialogues, a food bank. The gymnasium hosts basketball leagues. The library contains religious texts in multiple languages.

Tours are available daily, free of charge. You don't need to be Muslim to walk through the doors. The community actively encourages visitors from all backgrounds it's part of their philosophy. Sit in on a Friday prayer if you're curious. Ask questions. Nobody's going to look at you sideways.

What Alberta Looks Like Now

Drive through northeast Calgary today and you'll pass Vietnamese restaurants next to Ethiopian coffee shops next to Filipino grocery stores. The mosque fits right in. It's become a landmark, a point of reference when giving directions, a place where city councillors show up for iftar dinners during Ramadan.

This is what immigration actually looks like when the cameras aren't rolling. Not talking points or political footballs, but families building institutions, creating community spaces, putting down roots deep enough to last generations.

Baitun Nur will still be standing long after the arguments about multiculturalism fade from the news cycle. The minaret will keep catching the prairie light. And every Friday, the call to prayer will echo across Castleridge a sound that would have been impossible in the places these families left behind.